/Passle/5a1c2144b00e80131c20b495/MediaLibrary/Images/2025-09-04-13-22-29-684-68b992955a0e7c387a35c633.png)

Expulsion unlawful

10 minute read

The expulsion of a member of an unincorporated association was unfair and contrary to natural justice, but ultimately his remedy was minimal.

The High Court has held that a member's expulsion from a non-charitable unincorporated association was invalid because it did not follow principles of "natural justice".

However, the temporary suspension of a second member was not invalid merely because the member was not given prior notice of their suspension.

What happened?

Haque and anor v Faradhi and anor [2023] EWHC 1135 (KB) concerned the Muslim Community Association (MCA), a faith-based community organisation with many hundreds of members across the United Kingdom.

The MCA is now a private company limited by guarantee (MCA Limited) but, at the relevant time, it took the form of an unincorporated association. During this time, the MCA acted through an elected governing body, known as its Shura (or Shoora) Council and a Central President.

What is an unincorporated association?

An unincorporated association is, in essence, a group of persons who have come together to pursue specific non-business activities but have decided not to adopt a corporate entity for the purpose.

The association will have rules that set out its objectives, how it is governed and who takes decisions, how its property is held and managed, who can join and how, and how members can leave or be expelled.

Unincorporated associations are commonly used for charities, sports clubs and associations and other members' clubs. That the association's objectives comprise non-business activities is important. If the members instead come together to pursue a business for profit, their arrangement is more likely to be characterised as a partnership, with differing consequences.

Unlike companies and limited liability partnerships, unincorporated associations do not have separate legal personality and so cannot contract or hold property in their own name. Instead, they must act through one or more of their authorised agents. In effect, they are a "creature of contract".

This lack of legal personality can be awkward both for the association itself and for people dealing with it. As a result, it is not uncommon to see unincorporated associations convert into some kind of incorporated entity (normally, a company limited by guarantee) once they reach a certain size or need to conduct extensive dealings with third parties.

In late 2020, a member of the MCA and its Shura - Dr Haque - was suspended and, subsequently, expelled from the MCA on the grounds that he had used offensive language at a Shura meeting.

Dr Haque maintained that he had been suspended and expelled so as to suppress complaints of electoral malpractice in respect of a previous election for the Shura. In particular, he alleged that an element of campaigning had taken place during the 2019 Shura election, in breach of the MCA's constitution, which prohibited MCA members from canvassing support during elections.

Around the same time, another member of the MCA - Mr Rashid (who was not a member of the Shura) - was suspended and expelled for writing emails which the Central President considered to be offensive in tone.

Mr Rashid maintained that he had been raising concerns about an amendment to the MCA's constitution that prohibited members from communicating complaints or grievances, although he later also complained of electoral improprieties.

Dr Haque and Mr Rashid argued that:

- it was implied in the MCA's constitution that any decision to suspend or expel them must be taken in accordance with the "principles of natural justice"; and

- the decision to expel Dr Haque and suspend Mr Rashid had been taken contrary to those principles and, therefore, in breach of MCA's constitution (and so was invalid).

What are the "principles of natural justice"?

The phrase "natural justice" frequently arises in the context of making a formal decision, particularly one that has significant consequences for someone (whether an individual or a corporate). In that context, another way to refer to natural justice might be "procedural fairness".

This is relevant in circumstances such as those in this case, where someone is being expelled from a club, association, partnership, board, council or other grouping of persons. Other situations in which the principles of natural justice arise include:

- where a decision is being made to terminate a person's employment or impose disciplinary sanctions on an employee; or

- when making a finding that may result in restrictions or penalties being imposed on someone.

The demands of natural justice embody or incorporate legal principles that arise in other circumstances involving evaluative decision-making, such as in the process for judicial review of a decision by a public body, or when exercising a discretionary power under a contract (the so-called "Braganza duty").

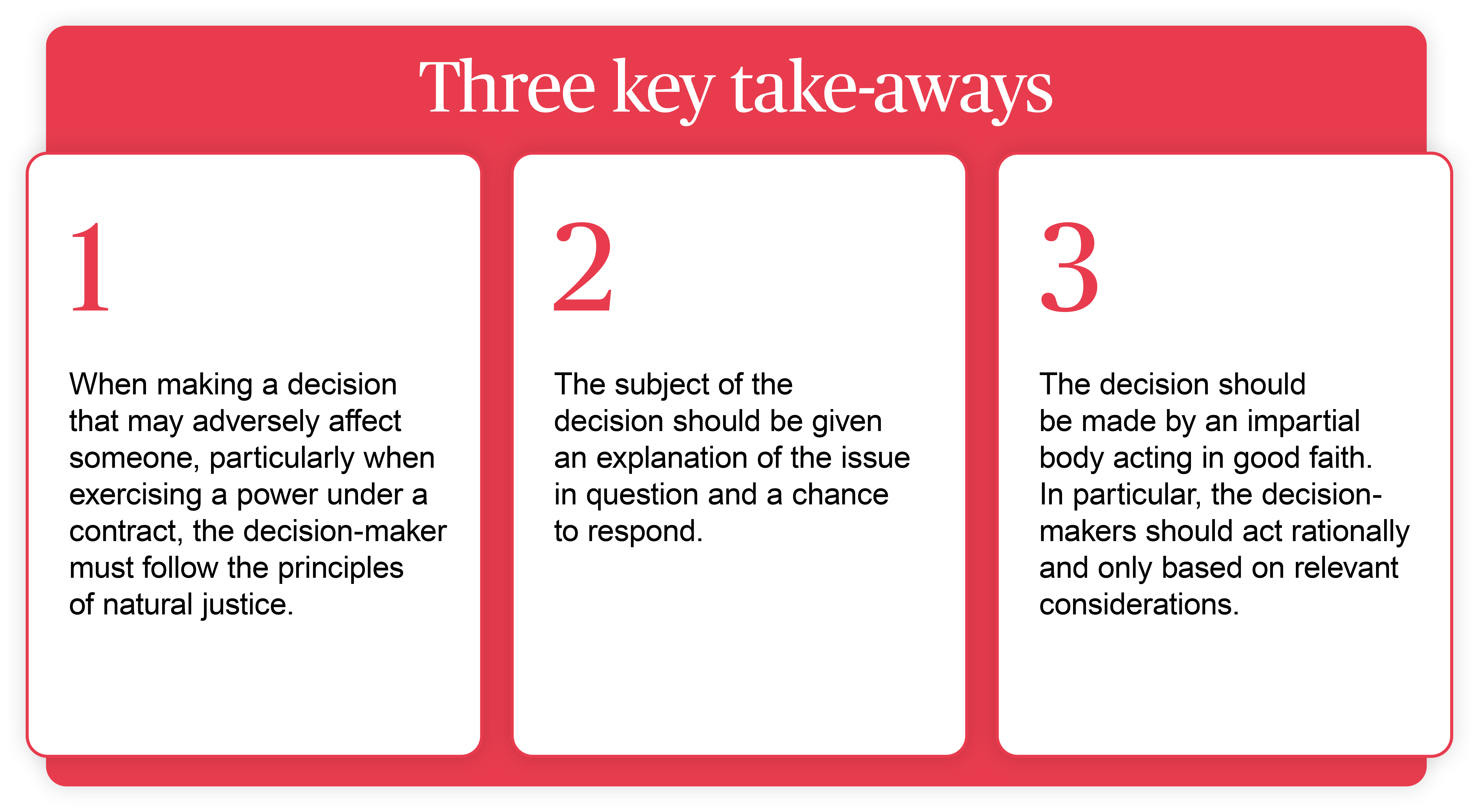

Fundamentally, natural justice requires a decision-maker (whether an individual or a body) to act fairly when reaching a decision.

Importantly, the precise principles that apply will evolve over time and always depend on each decision in its own context. As a result, it is impossible to set out a definitive list of principles. However, natural justice commonly includes the following requirements where a decision is being made that may adversely affect someone.

- The person potentially affected must be informed of the case they have to answer.

- They must also be given a fair opportunity to respond to those allegations.

- The person making the decision must be unbiased.

- The decision-maker must act in good faith and not for an improper purpose. In other words, they must not act on any of their own personal interests or motivations.

- The decision-maker must not act arbitrarily or capriciously. They must take all relevant factors into account and not base their decision on any irrelevant considerations.

- The decision must not be irrational. It cannot be a decision that no reasonable decision-maker could have made.

Importantly, natural justice is concerned with the procedure for reaching a decision, not the outcome. If a decision has been reached by an unfair procedure, the court may well strike the decision down. However, it will not make the decision for the parties. At most, it will require the decision to be re-examined and taken again but following a fair procedure.

The court and the parties agreed that principles of natural justice applied when deciding whether to suspend or expel a member under MCA's constitution, and the constitution contained implied terms to this effect.

It was therefore left to the judge to decide what those principles entailed and whether they had been contravened.

Were the suspensions unfair?

As noted above, Mr Rashid had argued that his suspension was unfair because he had been given no prior warning or opportunity to defend himself.

The court disagreed. The judge noted that MCA's constitution contained no procedure for giving a member prior notice of suspension, and that the Shura had a credible belief that Mr Rashid had been engaging in misconduct and breaches of MCA's constitution.

Dr Haque had not challenged his suspension. The judge nonetheless considered the issue and concluded that it was not unfair. He noted that compliance with MCA's constitution included abiding by Islamic principles and that the Shura had reason to believe that Dr Haque might have contravened one of those principles, namely the principle of avoiding gheebah ("backbiting").

As a result, both individuals' suspensions were valid.

Was Dr Haque's expulsion unfair?

Mr Rashid did not challenge his expulsion, so the final matter for the court was whether Dr Haque's expulsion had been carried out fairly.

The judge found that, in the circumstances, Dr Haque's expulsion was unfair and did not comply with natural justice.

The judge acknowledged that Dr Haque had not been singled out and had been given an opportunity to respond to allegations put to him before the Shura. However, he noted that an opportunity to make representations to a panel that "could be said to be biased or not suitably independent" may not be fair.

MCA's constitution envisaged that a hearing to examine the expulsion of a member could be held by a body other than the Shura. Dr Haque had specifically asked for any hearing to be conducted by an independent body, rather than the Shura, which he regarded as biased due to several Shura members being implicated in the potential electoral impropriety of which Dr Haque had complained.

The judge agreed that, in the circumstances, Dr Haque's request was a reasonable one for the Shura to accommodate. That is not to say the judge believed the Shura or any of its members were in fact biased, but rather that Dr Haque was entitled to a procedure that avoided any potential for bias.

In other words, Dr Haque had the right to protest his expulsion to people other than precisely those who had decided to expel him.

Importantly, the judge noted that it was not enough for Dr Haque to show that convening an independent body would have been fairer than allowing the Shura to hear his representations. Rather, he had to show that giving the Shura the final word was intrinsically unfair.

But the court decided that the inclusion of implicated members in the Shura hearing that would have heard Dr Haque's protests would have been inherently unfair.

However, for Dr Haque, this was something of a Pyrrhic victory. He had asked the court for a declaration that his expulsion was null and void (to the effect that he would have remained a member of MCA) and an injunction requiring MCA Limited to admit him as a member.

But the court said that, given the steps required and the state of the relationship between the parties, an injunction of this kind was "not a realistic option in the circumstances" and a declaration of the kind sought would not serve any useful purpose.

As a result, the judge was limited to awarding nominal damages in the amount of £100.

What does this mean for me?

On a technical level, the judgment highlights the importance of following a proper procedure when initiating any kind of disciplinary proceedings or any decision to suspend or expel someone from a body of persons.

Other than for trivial transgressions or in exceptional circumstances, it will normally be appropriate to follow an established procedure that ensures impartiality and affords the subject of the proceedings an opportunity to be heard. In this regard, there are certain steps that will or may prove useful.

- Assemble an appropriate decision-making panel. In particular, ensure that anyone involved in making the decision is free from potential or perceived conflict of interest or personal motivation.

- Set out the grounds of complaint. It is important to give the person to whom the decision relates the "gist of the case" they are being asked to answer. This may well involve difficult decisions on the extent of the documentary and witness evidence to be shared in each case.

- Give the person involved an opportunity to respond. The subject should have a reasonable period of time before the decision is made to make any representations. Whether this should be in writing or at some form of hearing, and the procedure to be adopted at any hearing, are important issues for the decision-maker(s) to determine.

- Document the decision. Set out the factors the panel has taken into account in reaching its decision, as well as any other evidence or arguments raised that the panel believes is immaterial or irrelevant. This should mitigate against claims down the line that the decision was taken improperly or irrationally.

- Provide reasons for the decision. Finally, give the person to whom the decision relates details of the decision, including how the decision was made and the reasons for it.

There is also a more pragmatic lesson from this case.

In his closing comments, the judge, Mr Justice Choudhury, comments that it was "lamentable that a dispute between members of a community organisation should ever have reached this stage" and "a matter of deep regret that [the parties'] differences could not be resolved without resorting to litigation".

Salutary though the judge's comments may be, the circumstances of this case are far from uncommon and this will not be the last time that a breakdown in relationships culminates in costly and time-consuming legal proceedings.

A desire for vindication may be well-intended and based on sound, technical grounds yet, as in this case, yield little in the way of practical compensation and merely serve to lay the disagreement bare to the world. The ardour of a perceived quest for justice can easily cloud a person's judgment, precipitating litigation when a private settlement or simple retreat might be the better option.

This is where the advice of a lawyer, who approaches a dispute with impartiality and detachment, can be most useful and prevent an aggrieved party from litigating needlessly.

Authors

Related topics

Like what you are reading?

Stay up to date with our latest insights, events and updates – direct to your inbox.

How can we help you?

Browse our people by name, team or area of focus to find the expert that you need.