The UK asset holding company regime: a quacking idea!

04 October 2021On 20 July 2021, the government published its response to a second stage consultation on a UK asset holding company regime along with some initial legislation for qualifying asset holding companies (QAHCs).

While this is not yet the last word (there is ongoing discussion and a significant number of points remain to be confirmed), we can at least begin to see the form which a UK asset holding company regime will take and an indication of the reliefs that will (and will not) be available. The bones of the regime are highly encouraging and what will now be key is to ensure that they are not fleshed out with too much complexity. If the regime remains simple (and some small issues are ironed out) this could be a game changing regime for the location of funds and their asset holding companies as long as the final niggles and unnecessary complications can be dropped or avoided.

Fans of the asset holding company regime will already be familiar with the first and second stage consultations which have preceded this latest publication. For the benefit of other readers, the use of asset holding companies by investment funds and institutional investors has long been a fixture of investment structuring for a number of tax and non-tax reasons.

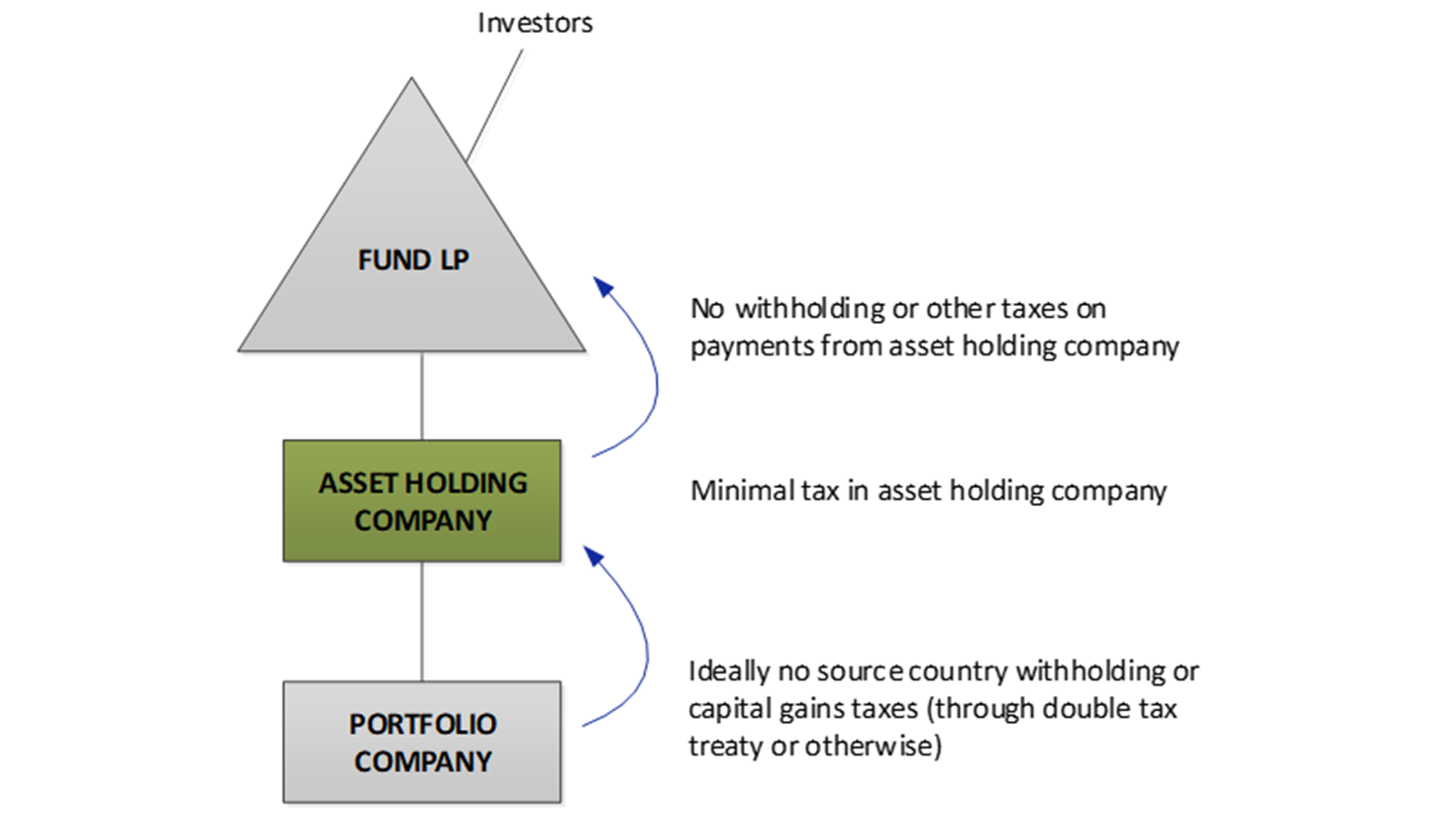

Most private funds (both private equity and other asset classes) tend to be structured as tax transparent limited partnerships formed to pool investment from (largely institutional) investors. These funds then go out and acquire assets, but they almost uniformly do so through a company in order to provide a liability shield (you don’t want your precious fund limited partnership entering into contracts with grubby counterparties) and to provide a platform for investments to be held and managed (i.e. through a board controlled by the investment manager). Importantly from a tax perspective, it is vital that this company (and indeed the fund, if it were to invest otherwise than through a holding company) does not cause an ultimate investor to suffer materially more tax than would have been the case had they invested directly in the underlying asset.

Therefore, an asset holding company needs to have (a) access to double tax treaties to ensure that there is no excess local taxation, and (b) a domestic regime which does not tax the asset holding company (or only to an extent commensurate with its intermediary role within the structure).

By far and away, the winning jurisdiction when looking for where to locate this asset holding company is currently Luxembourg. It has a broad double tax treaty network and has a system of effective (if sometimes complicated) reliefs to ensure that returns on investments do not suffer material tax on the way through.

The point of the proposed UK asset holding company regime is to enable a UK company to fulfil this same role. The government recognises that while this company may itself not pay very much tax (albeit some) the ability to base these structures in the UK will support the UK funds industry and provide an incentive for transactions to be structured in the UK where that otherwise makes sense (for example where the investment manager is based in the UK). This can be a win-win situation as revenue for the exchequer will be driven by increased activity in the UK (direct tax on the asset holding company itself as well as PAYE and other taxes driven by the economic activity here) while saving investment managers and their investors the (sometimes significant) cost of maintaining establishment and substance in Luxembourg.

The proposed regime

The regime which is proposed in the response to consultation and the draft legislation is, rather than making broader changes to the corporation tax rules for all, to introduce a regime for qualifying asset holding companies (defined as QAHC in the legislation and, with thanks to the parliamentary draftsperson, let us all now agree that this is pronounced "quack").

In order to opt into the regime a QAHC must be held at least 70% by good investors (referred to as Category A). This is a broad definition in the context of fund held companies and includes all collective investment schemes and alternative investment funds (CIS and AIF) which meet the conditions for genuine diversity of ownership as set out in the Offshore Funds (Tax) Regulations, SI 2009/3001 (slightly adjusted as it is for non-resident capital gains tax). Other "good" investors include life insurance businesses, REITs and overseas equivalents, pension funds, sovereign investors and other QAHCs. Therefore, while this definition will have to be closely monitored (and there are a few provisions and significant ongoing dialogue about preventing their use for avoidance), a typical fund structure should be able to use a QAHC.

Benefits of being a QAHC

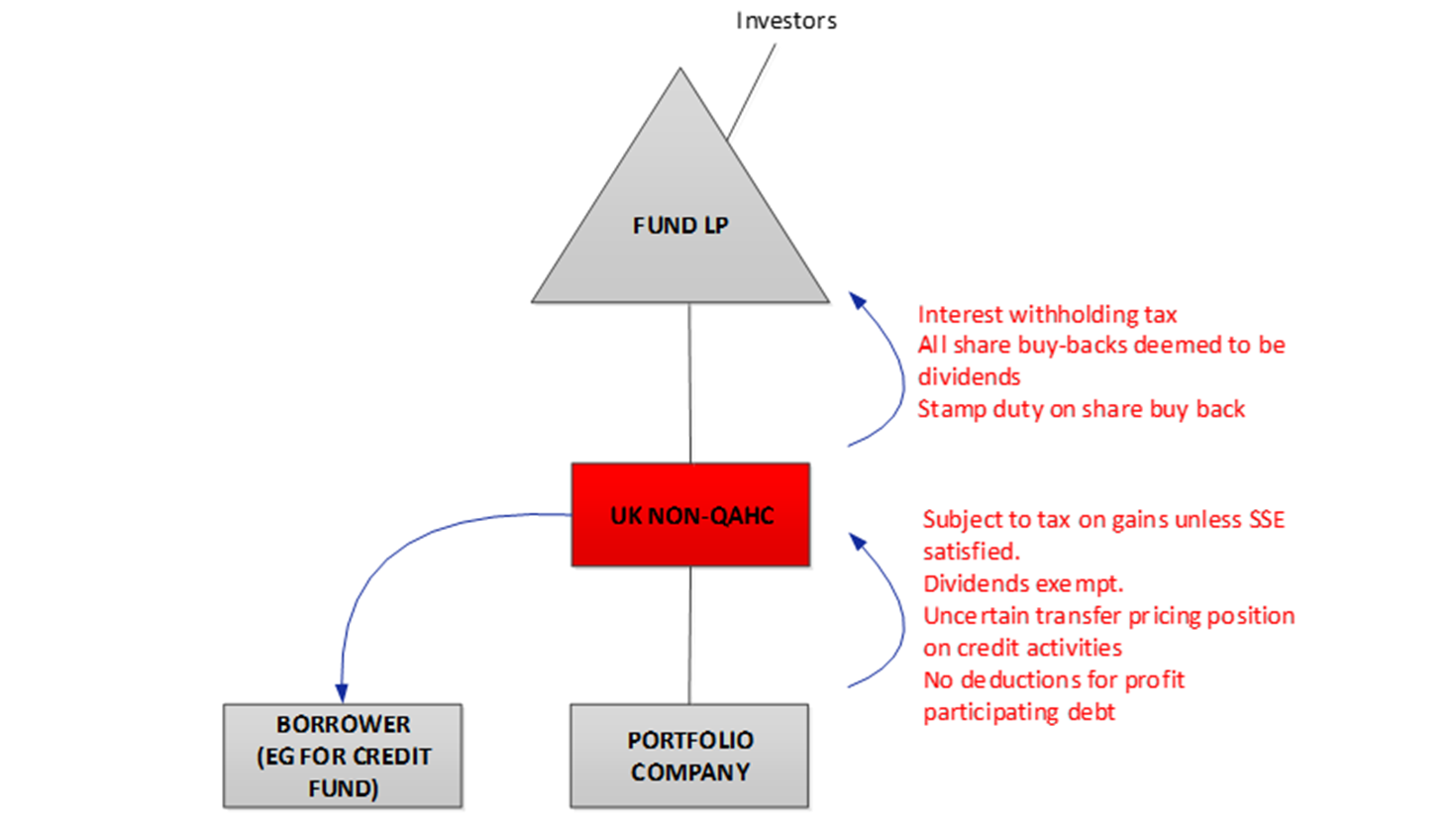

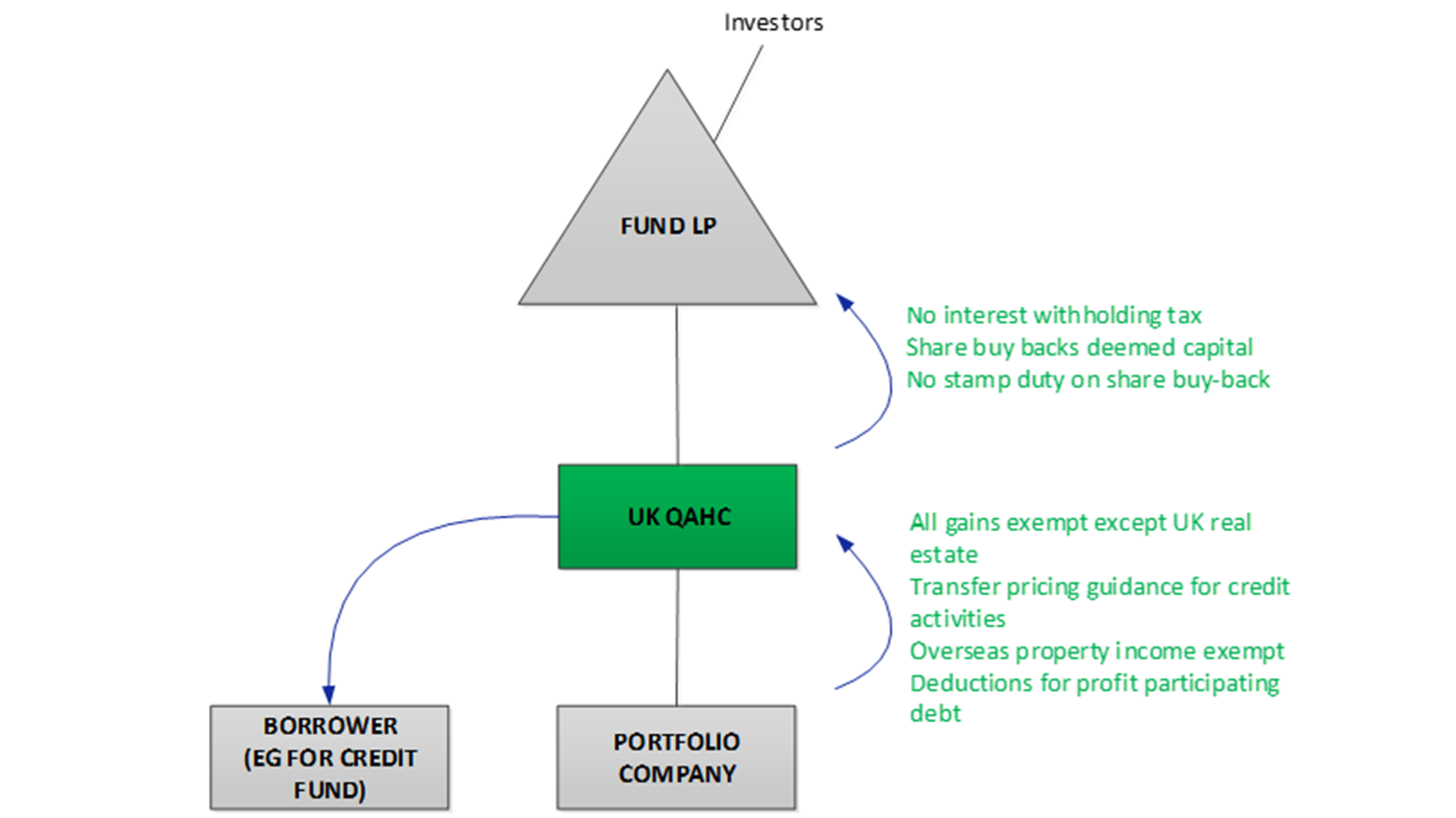

As shown in figures 2 and 3, a number of the existing issues with using a UK company as an asset holding company will be addressed by this legislation.

There will be a blanket exemption for capital gains received by the QAHC on the disposal of shares (other than in companies which are UK real estate rich) and overseas real estate. There will be no further conditions for this exemption to apply and so it will cover disposals of stakes of any size in companies irrespective of whether they are trading and irrespective of length of hold (so long as it remains investment activity and does not amount to a trade).

While the substantial shareholdings exemption has meant that many stakes in trading companies held by private equity would already have qualified (in particular, following the changes in 2017 to make it more widely applicable), most advisers know (and bear the scars) of the many pitfalls in that exemption. This change removes any doubt for a QAHC and also means that a QAHC can be used in non-trading PE contexts such as pan-European real estate investment. It also sets the UK regime ahead of the Luxembourg regime in that it can be used for stakes of any size held for any length of time. It will therefore also be helpful to credit funds that may hold equity kickers or warrants and for special opportunities funds which may dispose of equity shortly after having restructured a company’s debt; these are circumstances which are currently poorly catered for in any other jurisdiction.

To avoid a potential mismatch on the timing of taxation of a hedging instrument to manage forex exposure on acquisitions and disposals of shareholdings, the consultation response also raises the possibility of legislating to ensure that the treatment of gains and losses on the hedging instrument are aligned with the hedged item. This change would apply to all companies, not just QAHCs.

Interest withholding tax will not apply to interest paid on securities held by investors in the QAHC (note that this exemption does not apply to third party lenders). Although a policy decision has been made to limit the exemption, restricting the relief only to holders of relevant interests in a QAHC will, on the face of it, preclude withholding tax relief on payments of interest to other connected parties. It is hoped that the government will satisfy itself that there is no malice here, funding arrangements are commonly routed through group entities not within the AHC stack.

While the UK interest withholding tax rules already contain a number of exemptions, most notably the quoted Eurobond exemption, exempting QAHCs is very welcome as it reduces the complexity of operation and it also hopefully reduces the risk that fund holding structures get caught out by a tightening of the rules on withholding tax in other contexts (for example, the abolition of the quoted Eurobond exemption has long been Labour Party policy, but one might hope that would not apply to a specific regime such as QAHC).

The distribution rules will be amended to allow deductions for profit participating debt of an AHC, subject to usual transfer pricing principles.

This is particularly helpful in a credit fund context where an asset holding company is used as a finance company by the fund, reducing withholding tax complexity and serving as a single point of interaction with borrowers. Two key issues with using a normal UK company for these activities have been the inability to take deductions for profit participating debt which leaves only an arm’s length profit margin in the asset holding company and transfer pricing uncertainty.

These changes will address the latter, and, in the consultation response, the government has promised guidance on transfer pricing for QAHCs with financing activity to ensure that they only pay tax on a profit margin which is commensurate with what they contribute in their role as an intermediary holding company (i.e. not very much).

The late paid interest rules will also be disapplied to ensure that all deductions for a QAHC are allowable on an accruals basis. Further consideration is also being given to additional tweaks to the hybrid rules to ensure profit participating instruments are not inadvertently caught. However, there are no significant changes to the corporate interest restriction proposed (which should not be problematic since these changes are primarily to enable the operation of credit funds), although working through the operation of the rules in an QAHC context will be important.

One of the issues with existing UK asset holding companies is that any premium on a buy-back of shares is treated as a distribution in the hands of a UK individual shareholder and so taxed as dividend income. This is a major disincentive for UK individuals to use UK holding companies (not least the investment manager executives who have co-investments in the fund and also hold carried interest) since the effect of these rules could be to convert capital proceeds (for example from the disposal of an underlying investment) to dividend income.

The rules will be amended to ensure that share buy-backs by QAHCs will be taxed as capital. There will be rules introduced to ensure that these are not used to convert income into capital, but this is the subject of further discussion with industry (and a key area to watch as there is a risk of significant additional complexity if a simple solution cannot be found).

The proposals stop short of abolishing stamp duty on QAHC shares, as, whatever the merits, that would allow them to be sold and so save stamp duty, which is not within the remit of the proposals. However, it is confirmed that stamp duty and SDRT will not apply to share buybacks by a QAHC.

his is a hugely welcome new regime which addresses many of the issues faced by fund managers who wish to use a UK asset holding company. However, there are still some remaining "shoot in foot" opportunities that it is to be hoped the government and HMRC will resist.

Real estate and REIT points

As mentioned above QAHCs will be exempt on any gains on non-UK real estate. A broad exemption for rental income from overseas jurisdictions (provided it is also subject to tax) is also proposed.

What is clear is that no exemptions will be available in respect of investments in UK real estate (income or gains and irrespective of whether held directly or through a corporate), this was to be expected as it puts the QAHC in the same position as any other non-UK holding company. What is welcome is a confirmation that a QAHC can indeed hold UK real estate; it just won’t be able to access the exemptions. Therefore, a QAHC remains a sensible holding vehicle for a portfolio which includes UK real estate as well as other assets.

The proposals also include some changes to the rules for REITs which we address briefly here (real estate investment in light of the QAHC regime may merit a separate piece), albeit these do not go as far as had been hoped. A comprehensive review of the REIT rules is underway as part of the wider funds review, but in the meantime, there are two particularly welcome changes proposed.

First, the listing requirement will be dropped for those REITs which are 99% owned by qualifying investors (including limited partnership funds which meet the GDO tests): this will reduce the administrative burden of using REITs within fund structures.

Secondly, the "holders of excessive rights" rule (which penalises a REIT with corporate shareholders who own more than 10%) will not apply to holders of shares who are entitled to receive property income distributions gross. This is a short list, albeit including UK companies, and will not do much to reduce some of the challenges thrown up by this rule. There are also helpful changes proposed to the balance of business test and the definition of a foreign REIT equivalent.

Some other points to note

The legislation which has been provided so far only addresses a portion of the regime and is primarily addressed at the qualifying conditions, which as stated require 70% Category A investors. The percentages will be determined using the same rules as for consortium relief for corporation tax purposes.

Some other conditions need more work: for example, the consultation response mentions a need for any AIF or CIS to have an independent manager (which seems unnecessary given the GDO test). Recognising the inherent uncertainty with an activity test, the government is also working out how this condition can draw an appropriate distinction between investment and trading activity. On the credit side, there is a risk over-enthusiastic drafting could inadvertently determine activities such as loan origination to be classified as trading. A purpose test would be more helpful than any test that attempts to draw a bright line around certain activity.

There is also mention of a potential minimum capital raised for investment test of £50m to £100m. It is not clear whether this is to apply on a fund or on a QAHC by QAHC basis. We are aware that HMRC is discussing this with industry, but suffice to say that such a limit on the use of QAHCs would seem to constitute wilful self-harm to a regime which is otherwise so promising and (bizarrely) provide tax advantages to bigger funds at the expense of smaller funds – potentially driving them out of the market. Needless to say, this is an area which has been met with vehement opposition.

Another point still under consideration is the treatment of remittance basis users investing into a UK fund and QAHC and whether a form of business investment relief will be available to ensure this does not trigger a remittance. This is a point that has also been raised in the context of the wider review of the UK funds regime. It is to be hoped that it will be addressed as the need to accommodate high net worth investors, many of whom may be remittance basis users, is a key consideration in jurisdiction choice for many fund managers.

Entry and exit to the regime will be on an elective basis (unless the conditions cease to be met, in which case we expect a grace period) and will result in a deemed disposal and reacquisition of investments. Discussions continue on whether there will be a waiver of the 12-month holding period requirement for SSE on existing companies entering into the regime and on the rules around accrued and unused losses on entry and exit from the regime.

Final thoughts

In summary, therefore, this is a hugely welcome new regime which addresses many of the issues faced by fund managers who wish to use a UK asset holding company. However, there are still some points of detail to be worked through and some remaining "shoot in foot" opportunities that it is to be hoped the government and HMRC will resist.

This article was first published by Tax Journal.

Get in touch